The Museum is home to Grant County’s very own Runestone, known as the Setterlund Runestone. It is a heart-shaped rock with a runic inscription “1776 Four maidens set camp on this hill” carved on the flat face of it. It is named the Setterlund Runestone for Victor Setterlund, a farmer living in Elk Lake Township in Grant County, Minnesota. Because Setterlund firmly believed that the Kensington Runestone was a fake and not only did he believe the Kensington Runestone was a fake, he declared that he knew the man who had forged it. With this in mind, he determined that he could make a runestone much more accurately.

Victor Setterlund had only completed second grade, leaving to work on his father’s farm. He taught himself to read, enjoyed reading, and was quite knowledgeable about Scandinavian history and language. Victor found a heart-shaped flat stone, armed himself with a book, “Lasebok for Folksakolan” [Reading Book for Public School] containing the runic alphabet and number system, forged a set of punches using his blacksmithing experience, and set to carving. When finished, he “aged” the carving with acid (another account says it was “aged” in a manure pile), set the stone by his house, and awaited someone to take an interest in it.

In 1949, an automobile salesman from Elbow Lake was shown the stone and set off a flurry of interest as reported in the Grant County Herald. Setterlund did apparently change where he found it from his farm field to a local hill known as Junfra Haugen (Maiden Hill) and was economical with the truth, failing to mention that there was no carving on it at the time. He also refused to sell it, not wishing to defraud anyone.

In 1949, an automobile salesman from Elbow Lake was shown the stone and set off a flurry of interest as reported in the Grant County Herald. Setterlund did apparently change where he found it from his farm field to a local hill known as Junfra Haugen (Maiden Hill) and was economical with the truth, failing to mention that there was no carving on it at the time. He also refused to sell it, not wishing to defraud anyone.

As hoped, the experts arrived. A highly skeptical J.A. Holvik, Professor of Norse at Concordia College, Moorhead, MN translated the runic inscription. Setterlund had intended the date to be 1876, which would have made the inscription an obvious fake. However, he inadvertently omitted a third horizontal bar on the “8”, which made it a “7”, and Holvik correctly translated the date as written to be 1776, which was still highly improbable.

A second expert, Professor H.A. Holand of Ephriam, Wisconsin, was considered the authority on runes in the country. He had made a long study of the Kensington Runestone and was far less skeptical. In his translation from a plaster cast of the stone, he mistranslated the first “7” in the date as a “3”, making the date 1376. This date was intriguingly close to the date on the Kensington Runestone, further muddying the waters.

Professor Holvik’s second examination of the stone and a meeting with Victor Setterlund got to the bottom of things. After some questioning, Holvik directly asked Setterlund if he had carved the stone. Victor answered “yes”. Holvik then asked “Why didn’t you tell us before?” “Nobody asked me,” Setterlund replied.

The Setterlund Runestone is displayed in the Grant County Museum through the efforts of W.M. Goetzinger, who also furthered the research by having Setterlund give a deposition in 1965 relating his carving of the runestone.

Although the Setterlund Runestone with its runic inscription is a fake, it is also a tribute to the ingenuity and skill of Victor Setterlund.

By Don McCollor 3.17.22

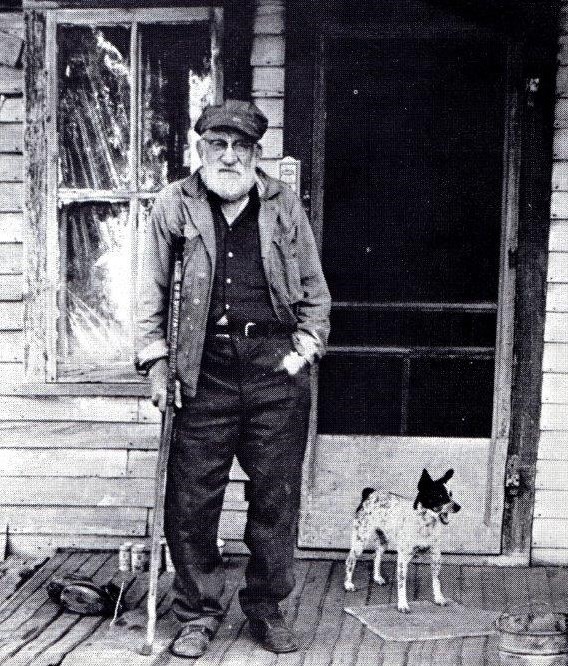

Photo by Tom Grout

SOURCES

The articles from the Grant County Herald, the Affidavit/Deposition, the Theodore Blegen letter, and the Reading Book for Public School can all be found at the Grant County Museum.

Grant County Herald August 11, 1949 “Runestone Found”

Grant County Herald September 26, 2001 “Victor Setterlund was a figure in Runestone controversy”

Grant County Herald October 3, 2001 “Corrections and additions – Barrett Runestone”

Grant County Historical Society archives. Affidavit of Victor Setterlund May 9, 1965 witnessed by W.M. Goetzinger, Notary Public.

Grant County Historical Society archives. Letter from W.M. Goetzinger to Dr. Theodore Blegen, Minnesota Historical Society December 7, 1964.

Other Sources

Nielsen, Richard and Wolter, Scott F., The Kensington Rune Stone – Compelling New Evidence, Lake Superior Agate Publishing, 2006, 574 p. “The Historical Timeline for the Kensington Rune Stone” pp. 447-450.